The books that carried me through 2025

How fiction, history, and presence shaped a difficult and good year

Hello Sardines,

This issue is a little different from our usual essays. As I reflect on 2025, which was both the most difficult and also one of the best years I’ve experienced (more on that later), I found myself looking back at the books I read and reread along the way. What follows are my top picks from the year.

You might use this list to spark a new read or to finally pick up a book you might not have chosen otherwise. In the comments, I’d love for you to share your favorites too, so we can start building a collective shelf for 2026.

Fiction

As I’ve progressed in my reading life, I’ve steadily made more room for fiction. These books tend to outlive the expiration dates of most non-fiction, especially self-help or trend-driven works. Fiction has also quietly shaped modern innovation, from why we call the Metaverse what it is (Snow Crash), to Grok AI (Stranger in a Strange Land), to early explorations of blurred lines between humans and machines (Isaac Asimov’s “Evidence”), to name a few.

Here are some of my favorite fiction reads from this year.

Stoner — John Williams

Stoner follows William Stoner, a quiet Missouri farm boy who becomes a literature professor and lives a life defined more by endurance than achievement. Through failed love, professional disappointment, and private devotion to learning, the novel shows how an apparently ordinary life can carry profound moral weight.

I picked this up after seeing it go viral on X multiple times. Once I started, I couldn’t put it down and finished it in a couple of sittings. I agreed with much of what people said about it, but I also saw myself in it in ways I didn’t expect. It’s the kind of book that stays lodged in your mind long after you close it.

What continues to linger are the layers. I keep thinking about the two kinds of dying Masters talks about, and how different characters throughout the book seem to embody those deaths in their own way. I’m still turning over what it means that Stoner is so often aware of his own voice, how it falters, disappears, or slips out of his control, and how closely that mirrors his life.

Even small details feel intentional, like how Williams introduces so many characters through their glasses, frames, and lenses. I’m not fully sure what to make of that yet, but it feels like a quiet signal about perception and distance.

And then there’s love. Romantic love, yes, but also the quieter kinds, between parent and child, and between a person and their work. That final reflection on Gracie, “you were always there,” hit me harder than I expected. It felt like the novel admitting that presence itself can be a kind of success.

Honestly, it’s a lot to process. That’s what makes it one of the most layered and deeply affecting novels I’ve read in years.

Children of Time — Adrian Tchaikovsky

Children of Time is a science fiction novel about humanity struggling to survive extinction while confronting intelligence that evolves in an unexpected form.

The story unfolds across two timelines. In one, the last remnants of humanity travel aboard a generation ship searching for a habitable world after Earth’s collapse. Political tension, failing systems, and competing visions for the future threaten the mission from within.

In the other, a failed terraforming experiment accelerates the evolution of spiders on a distant planet. Over thousands of years, they develop language, technology, religion, and social structures that reflect a form of intelligence radically different from human norms, yet internally coherent and adaptive.

I listened to this as an audiobook and highly recommend experiencing it that way. What stayed with me most was how the novel shows humanity trying to control the future, only for nature and reality to produce something entirely different. Very much in the Jurassic Park sense that life finds a way, just not in the way you expect.

Project Hail Mary — Andy Weir

Project Hail Mary follows a lone astronaut tasked with saving humanity, even though he wakes up alone in space with no memory of who he is or why he is there.

As Ryland Grace regains his memories, he learns that Earth is facing extinction due to a mysterious organism draining energy from the sun. Chosen for a last-resort mission with no plan for return, he must rely on science, ingenuity, and persistence to give humanity a chance.

What I enjoyed most was how the book gives genuine humanity to alien life and treats the unknown with curiosity rather than fear. Watching two species struggle to understand one another and slowly break barriers became the emotional core of the story for me.

If you’re a fan of The Martian, you’ll find similar themes here. I’m also looking forward to seeing how the 2026 film adaptation brings that partnership and sense of wonder to the screen.

Electra — Sophocles

Electra is a Greek tragedy centered on grief, justice, and the cost of revenge within a broken royal family.

After the murder of her father Agamemnon by her mother Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus, Electra lives in mourning and humiliation at the palace in Mycenae. She refuses to forget the crime, clinging to grief as both resistance and identity.

I wanted to experience this family tragedy from Electra’s perspective, rather than through works like The Oresteia or The Odyssey, which frame the story more broadly. Through Electra’s eyes, every version of justice carries a different moral weight.

By staying close to her voice, Sophocles forces us to confront what it truly means to enact revenge, and to ask whether justice achieved through blood can ever come without unbearable cost.

Doctor Faustus — Christopher Marlowe

Doctor Faustus is a Renaissance tragedy about ambition, knowledge, and the danger of wanting more than the human condition can safely hold.

Faustus, dissatisfied with traditional learning, turns to magic and makes a pact with Mephistopheles, trading his soul for twenty-four years of power.

I reread this after being inspired by it multiple times while writing The Faustian Bargain of AI. Returning to the text reminded me how much there is to relearn from great works when viewed through different lenses. Faustus’s wavering between repentance and pride feels newly relevant in an age that rewards speed, power, and certainty over restraint.

Non-fiction

Non-fiction tends to fall into two categories for me: timely and timeless. Timely works are often stretched beyond their core idea, better suited to essays than full books. Because of that, I read fewer new non-fiction releases and often turn to podcasts for emerging ideas, revisiting books only if they still resonate years later.

Timeless works are different. I gravitate toward recent history, ancient history, philosophy, theology, memoirs, and classics. These stood out most this year.

Peak Mind — Amishi P. Jha

Peak Mind is a science-backed guide to understanding attention, why it fails under stress, and how to rebuild it through short daily practices.

This year, I made a conscious effort to simplify my thought life. My mind felt constantly pulled in too many directions. This became one of the pillar books that helped ground my thinking and restore a healthier relationship with attention.

Its emphasis on presence over productivity, and clarity over hype, makes it especially effective.

Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World — Mark Kurlansky

This narrative history traces how a single fish shaped global trade, exploration, empire, and modern capitalism.

I enjoyed Cod not only for its subject, but because it connects directly to my family heritage in northern Spain. I’m drawn to micro-histories like this, deep dives into one ingredient or object that reveal how much of the world unfolds from it.

That’s how Mark Kurlansky became one of my favorite authors almost by accident. I picked up several of his books based on theme alone, only later realizing they were by the same writer. The Basque History of the World is another favorite, and next up are Salt and Salmon.

Hitler, My Neighbor — Edgar Feuchtwanger

This memoir recounts the author’s childhood growing up Jewish in Munich while Adolf Hitler lived just down the street.

What makes it powerful is its restraint. Life narrows gradually, restrictions accumulate, and fear becomes ambient rather than dramatic.

Coming from a refugee family, what stayed with me was how easy it is to remain in a threatening situation when daily life still offers familiarity and security. The book is a sober reminder that when something feels deeply wrong, seeking safety while it is still possible can matter more than preserving what feels familiar.

Quantum Supremacy — Michio Kaku

This book explores how quantum computing could transform science, medicine, energy, cryptography, and artificial intelligence.

I didn’t understand everything, but it helped me finally grasp what quantum computing is and how it may shape the world ahead. It feels both like an invitation and a warning, suggesting that understanding new technologies early matters as much as how we choose to use them.

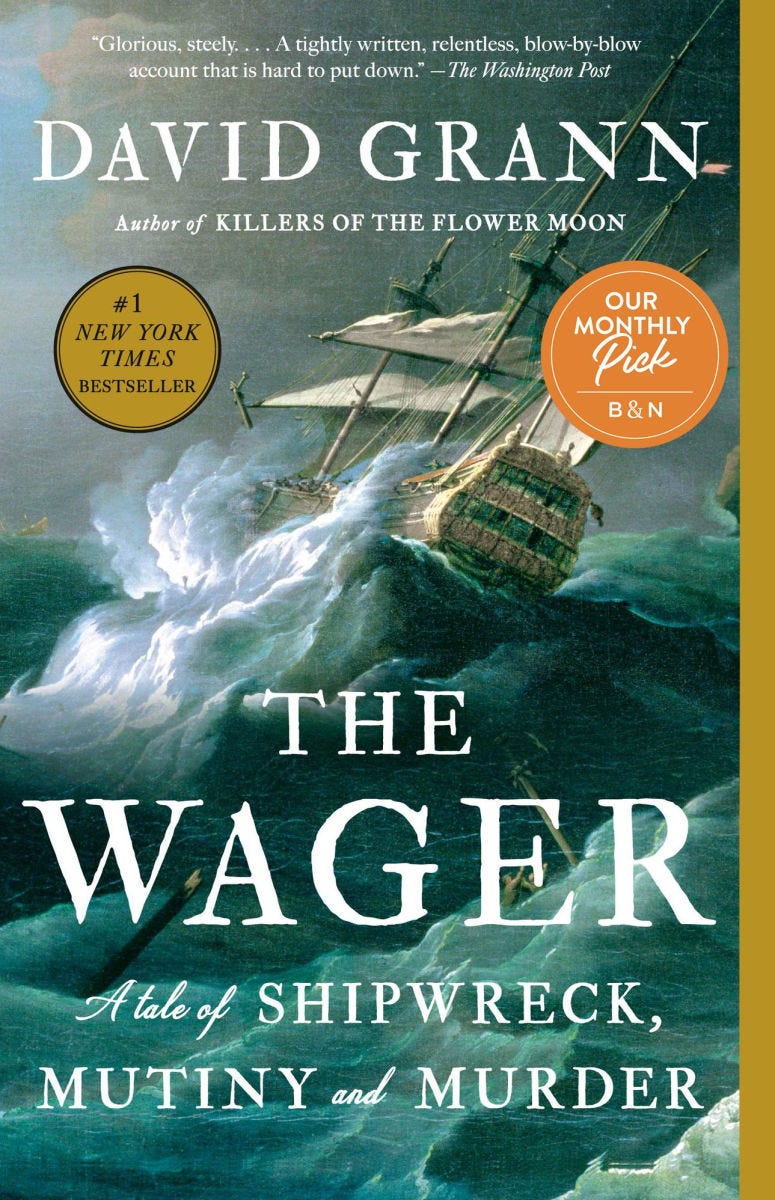

The Wager — David Grann

The Wager reconstructs one of the most harrowing naval disasters of the eighteenth century.

I first read it while writing The Math of Missing, but I directly reflected on it later while working on The Discipline of Not Acting. What stayed with me was how easily the wreck could have been avoided if the captain had listened to wise counsel and paused to reassess.

It’s also a genuinely adventurous read, filled with momentum and well-placed cliffhangers that make it hard to put down.

The Sweaty Startup — Nick Huber

The Sweaty Startup argues that wealth is more often built through unglamorous, service-based businesses than through flashy startups.

I listened to the audiobook while staying in La Herradura near Málaga. It helped me think more creatively about the opportunities around me, especially the ones that are overlooked because they aren’t celebrated in business magazines or on LinkedIn.

The Practice of the Presence of God — Brother Lawrence

This short spiritual work centers on cultivating awareness of God through everyday life.

As part of my effort to renew and simplify my mind, this became a favorite. Lawrence, a monk in the 1600s, held no grand position. He was a shoemaker, yet his way of living left an impact that endures centuries later. A quiet reminder that a meaningful life can be nurtured in any situation.

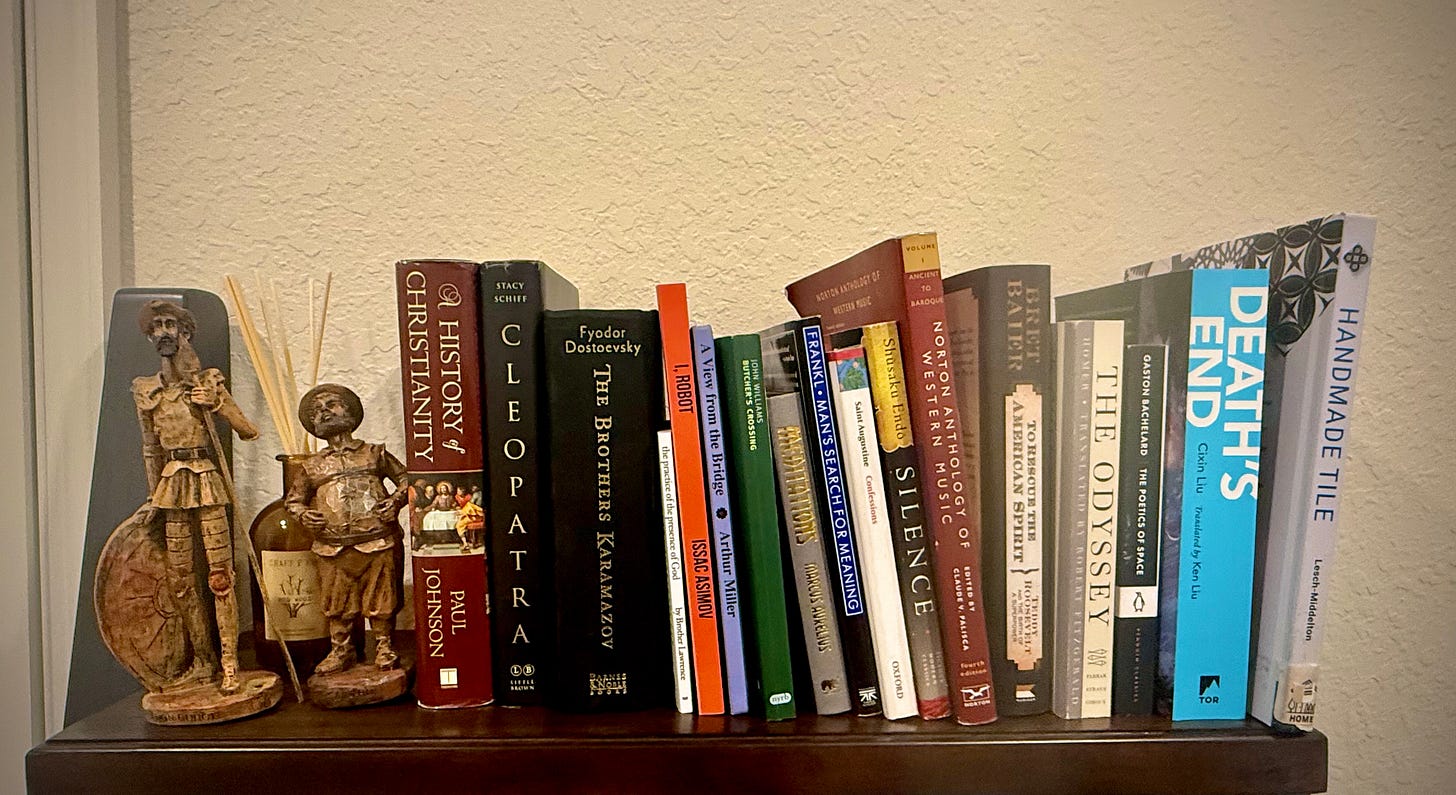

These were some of the books that shaped my 2025. I already have a growing shelf for 2026, including reading The Brothers Karamazov for the first time and finishing the Three-Body Problem trilogy with Death’s End.

What did you read in 2025, and what are you looking forward to in 2026?

i've got a stack of fiction / nonfiction that i'm working through this year. adding "Stoner!"