The Faustian bargain of AI

What we risk when we outsource thinking

Christopher Marlowe, the author of Doctor Faustus, never lived to see his play published or performed. He was murdered after a dispute over a bill spiraled out of control, ending in a fatal stab to the eye. He would never see how Doctor Faustus would live on for centuries. In a modern sense, we too may never fully grasp the long-term consequences of today’s technologies—AI included, for better or worse.

This social contract we are signing between artificial intelligence and the human race is changing life rapidly. And while we can guess where it takes us, we aren’t entirely sure. Instead, we can look to the past to find truth.

Take the COVID-19 pandemic, for example. As rumors of shutdowns began to swirl, I found myself reaching for Albert Camus’ The Plague. Long before we knew what was coming, Camus had already offered a striking portrait of the very world we were about to enter: lockdowns, political division, and uncertain governments.

Just as Camus captured the psychological toll of unseen forces, Marlowe explores the cost of human ambition when we seek control over the uncontrollable. Why did Faustus give up his soul? Why did he cling to his pact, even as doubt crept in? And what did he gain, briefly, in exchange for something eternal?

In Marlowe’s tragedy, we find a reflection of our own choices as we navigate the promises and perils of AI.

II. The pact, ink, and blood

Doctor Faustus tells the story of John Faustus, an ambitious scholar who grows disillusioned with traditional knowledge and turns to black magic. He summons the demon Mephistopheles and makes a fatal bargain; in exchange for twenty-four years of power, knowledge, and service, he will surrender his soul to Lucifer. Faustus, we learn, is attracted to unbridled power:

“All things that move between the quiet poles

Shall be at my command. Emperors and kings

Are but obeyed in their several provinces

But his dominion that exceeds in this

Stretcheth as far as doth the mind of man;

A sound magician is a demi-god!

Here tire my brains to get a deity!”

Like Faustus, we too have summoned a new kind of servant: artificial intelligence—a technology that promises knowledge, productivity, and control beyond human limits. But every act of creation carries a hidden cost; dependency, distortion, or the loss of something essential—even obsession, as Faustus puts it when he says, “’Tis magic, magic, that hath ravished me!”

III. The illusion of knowledge

When you log into ChatGPT, the search bar says “Ask anything.” Grok says “What do you want to know?” And Mephistopheles asks Faustus, “What wouldst thou me do?”

This unlimited source of knowledge and capability masks its immediate downsides. Faustus, too, fell for the illusion of power. And today’s AI users are often no different.

MIT Media Lab released a 2025 study examining AI’s impact on the brain. When researchers analyzed how students wrote SAT essays using AI tools, they found that participants “consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels.”

This kind of outsourcing forces us to ask: what exactly do we want from AI? A quick, effortless answer? Or deeper, more meaningful experiences that enrich our lives? In Doctor Faustus, there’s a telling moment: when Faustus signs his pact in blood, the ink clots and congeals. It’s as if something, or someone, is warning him to stop; a hesitation, a final chance to choose differently. He says, “My blood congeals and I can write no more.” Mephistopheles then assists Faustus so he can continue.

These questions on outsourcing output remind me of what Ezra Klein, the co-founder of Vox, said on David Perell’s podcast, How I Write:

“I thought that reading was about downloading information into your brain. And now I think that what you’re doing is spending time grappling with the text. Making connections. That’ll only happen through that process of grappling.

Part of what’s happening when you spend seven hours reading a book is you spend seven hours with your mind on a single topic. The idea that [ChatGPT] can summarize it for you is nonsense. ChatGPT outputs don’t impress themselves upon you. They don’t change you.”

It’s perhaps this wrestling with content and life experiences that provides the real value, not just knowing a few broad strokes of a subject.

An X user, Erik Rostad, echoes this sentiment when he said of reading Sophist by Plato:

“I’m having so much trouble following this dialogue. My mind wanders and I lose track of the argument. I’m on my second reading and am just as lost as the first reading. Any suggestions for understanding what’s happening here?”

As Rostad searches for advice and as he works through these challenges, he’ll grow across multiple dimensions: philosophically, personally, and intellectually.

Quite interestingly, Sophist centers on a type of teacher-like figure who may, in fact, be a deceiver. The dialogue explores the many roles a sophist might play, from someone who merely appears wise to one who sells knowledge without possessing it. And that ambiguity often mirrors what we see with AI-generated output. Plato himself warns us about this illusion of understanding. The philosopher writes in Sophist:

“When a person supposes that he knows, and does not know; this appears to be the great source of all the errors of the intellect.”

Perhaps the greater danger isn’t believing something false, but believing you understand something deeply when you barely know it at all.

I was recently talking with a friend, for example, about AI workflows. When he asked what I thought about using AI for content production, I told him that content—or code, or any kind of output—is just the end result of pattern recognition across massive datasets. In other words, it’s built on what’s common, familiar, and often overdone.

Yes, someone can take that AI-generated article, refine it, and add insights to it. But it’s like building with sticks. You might use better glue, but you’re still working with the same old sticks; shallow work.

Throughout twenty-four years, Faustus too wastes his gift on shallow displays—like summoning Helen of Troy, mocking the Pope, and performing cheap tricks—instead of pursuing meaningful things (but can you with that kind of pact?).

Today, we often use AI for similar spectacles: endless content, optimized clicks, and superficial replication. Instead of deep understanding, we chase novelty and efficiency. Like Faustus, we risk turning miraculous potential into a trivial distraction.

Over time, we may not just misuse AI. We may forget why we built it in the first place.

Take, for instance, E.M. Forster’s The Machine Stops. The short story is about a machine running an underground civilization. After many generations, there are kinks and glitches that threaten the underground society. But the engineers are long gone, and so are the knowledgeable repairmen. This new generation doesn’t understand the machine and therefore worships it as a god—despite its malfunctions.

With AI, as users explore the technology like Faustus did with his abilities, and as they outsource their thinking, they risk becoming less human and less capable of real creativity, innovative solutions, and purpose.

Does AI inevitably lead to shallow thinking? No. But the depth of our thinking depends entirely on how we choose to use it.

IV. The soul at stake

Like Faustus, we may realize too late what we’ve given up in the pursuit of ease and control. As Faustus’s time runs out, and though he briefly considers repentance, despair overtakes him. In his final, desperate soliloquy, he faces the horror of damnation as demons drag him to hell, revealing the tragic cost of pride, unchecked ambition, and defiance of divine order.

The ‘soul’ here is metaphorical—what we stand to lose if we’re not careful: autonomy, discernment, identity, originality. Humanity still has time before its own final soliloquy. The question is whether we’ll use AI to amplify our efforts or let it hollow out our will to think. Faustus’s tragedy was in undervaluing what he traded away. His soul. His eternal life. His relationship (if any) with God.

Yet, as the doctor grew closer to his approaching doom, angels reminded him it was not too late to repent. This is a notable theme in Marlowe’s play. It’s not too late—until it is.

Beware: technologies like this will always tempt you to trade something precious (even without knowing it). It was Mephistopheles who told Faustus in some of their final conversations that it was he who:

“Dammed up thy passage. When thou took’st the book

To view the Scriptures, then I turned the leaves

And led thine eye.”

AI has changed everything in just a few years, costing some people their jobs and leaving many others afraid to lose theirs too. Industries are dying, and industries are budding. As Isaac Asimov puts it, “Science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.” But one thing remains: we can slow down.

We can decide how we will adopt AI’s influence, how to limit its negative effects, and how to use it for good.

V. A wiser kind of magic

In my essay Going Analog, I discuss how choosing simpler aesthetics—like an old radio or a dumb phone—can facilitate meaningful purpose in our lives by distracting us less from what is true and real. This is the same for AI.

Artificial intelligence can be our helper, not our pilot. We must be intentional about outsourcing some parts of our lives, but not all of them, and not all the time. Put simply, we must view the AI-mind relationship like we do with physical activity and transportation.

We can drive a mile, for example, which is more efficient, but we sacrifice our health. In rare instances, driving a mile might make more sense because we’re running late or in a hurry. But as a long-term habit, walking a mile will be more beneficial to our health.

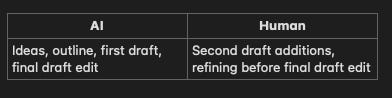

If, as MIT Media Lab found, AI negatively impacts cognitive ability, then we must choose when and when not to use AI. What I have found helpful is to view AI use as a hybrid experience—a human-powered process, assisted by AI.

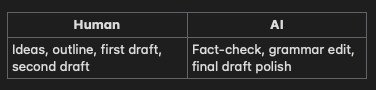

For example, an AI-first process for a marketer developing a blog article may look like this:

The problem with this approach is that it’s an AI product with human refinement. The ideas are not original. Even if the human adds some of their experiences and insights, it’s built on an AI foundation developed from millions of data points—it’s redundant.

Instead, the marketing professional in this case can do as Ezra Klein implies and wrestle with ideas, a first draft, and an outline. These ideas are true, real, and original to the author. No AI can generate this from scratch. Not only does this make for a better blog post, but it also allows the author to exercise her mind, become better at her craft, and publish unique, one-of-a-kind material.

Here’s what the AI-powered human approach looks like:

Now the roles have been reversed.

The human is the thinker and the writer. The AI becomes the assistant, offering tweaks and edits, while the writer stays in control, retaining originality and cognitive engagement.

Not only is this approach helpful in a professional setting, but it’s also helpful in personal life. Instead of Googling or asking LLMs like Grok what kind of bird you’re looking at outside, for example, you can force yourself to study and analyze the bird; take note of its colors; and use deductive reasoning to guess what bird it may be.

This forces you to live in the present and exercise your mind, digging through your memories to provide the most educated guess you can. Only then should you have a conversation with AI. You’ll find that you remember this new information more easily, benefit from technology, and exercise your mind.

i’m actually speechless at this, it is obviously beautiful but the talent you have to even conjure up such a comparison is unbelievable to me.

Wow, the part about the social contract we're signing with AI really hit home. That line 'we too may never fully grasp the long-term consequences of today’s technologies—AI included, for better or worse' truly echos my own thoughts. It captures that unease I often feel as a CS teacher looking at what's next. Such a thoughtful piece.