The math of missing

Why missing your shot is part of the equation

Last weekend, I was reading a book about the sea while lounging on Florida’s Space Coast, waiting for a Blue Origin launch. A photographer had unpacked his gear nearby and stood there for hours, camera straps and lenses hanging off him like armor.

My family and I met up with my sisters’ families for a birthday. We played cards, swam, ate bocadillos and grapes and chips, and the whole time he never sat down—just watched the pad from a distance, waiting through delay after delay.

Each time poor weather pushed the launch another thirty minutes, he stayed put. I offered him a seat, but he only thanked us and kept standing, steady and focused. Eventually, weather and a cruise ship in the launch zone canceled the window.

The photographer took a long breath, brushed off his shoulders, and said, “‘Til next time,” before packing up his gear.

Sometimes what you want won’t happen when you want it. But most of the battle is simply being there. When opportunity comes, you’re not “lucky overnight”—you were already prepared.

So when we miss our shot, how do we keep going? Missing isn’t the opposite of success. It’s part of the equation; every attempt teaches you how to aim.

II. When winning looks like losing

Watching that photographer wait all day made me think of another kind of perseverance—the kind Anthony Hopkins writes about in his memoir, We Did OK, Kid, and the long, unglamorous act of showing up again and again, even when the moment keeps slipping.

In the memoir, Hopkins doesn’t frame his life as a string of triumphs but as a long conversation with failure, or rather, with the self that failed and kept going anyway.

He writes about being that awkward Welsh kid, dyslexic and adrift, watching the world move faster than he could. For him, acting wasn’t destiny; it was a refuge from isolation. Even his career’s biggest leaps were tangled with doubt and self-sabotage. You get the sense he never really believed in “missing his shot,” because every mistake, every relapse, every silence became raw material for the next act.

That’s what makes Hopkins’s story powerful. It’s not the story of a man who conquered his demons but one who learned to live beside them. He explains this mindset through his approach to acting in his memoir:

“Becoming familiar with a script was like picking up stones from a cobblestone street one at a time, studying them, then replacing each in its proper spot.”

Life works like that, too. We’re given the stones scattered on the ground. We pick them up, one by one. Some fit, some don’t. But it’s a process, a puzzle, a kind of assembling.

And in each miss, there’s something to gain.

III. What you gain by getting it wrong

Missing a shot is a necessary step toward success. It’s the journey that shapes who you become as a person, an artist, and a professional.

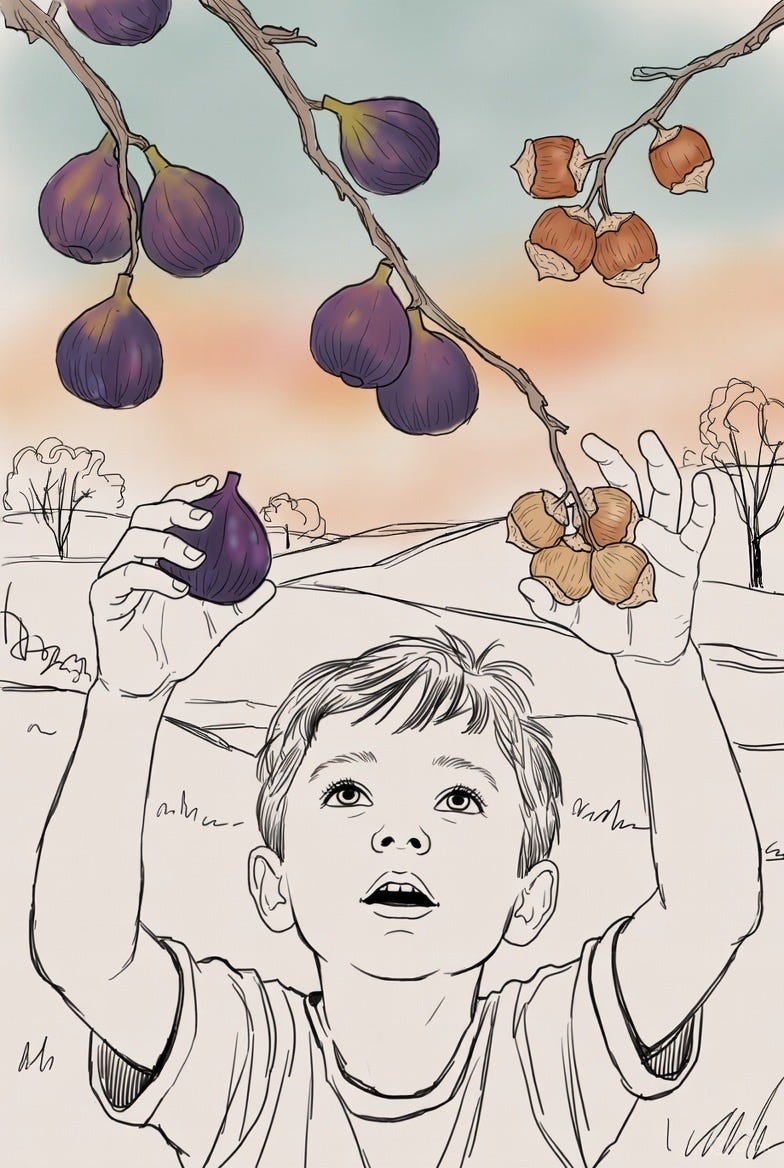

In Aesop’s fable The Boy and the Filberts, a boy grabs as many figs and filberts (hazelnuts) as he can, then can’t free his hand from the pitcher. The advice is simple:

“Grasp only half the quantity, my boy, and you will easily succeed.”

Accepting limits becomes the way forward.

The wise person documents those learnings. Sometimes we play the fool and refuse to examine what we’ve done; we repeat the same misses until, perhaps, we finally understand. Even with the best intentions, we are not immune to foolishness. Stress and pressure get in the way. In anxiety and self-doubt, we fail to stop and reflect.

When you miss the mark, there’s also a moment to acknowledge where you are. You have the chance to try again, to breathe another breath. This is a gift and should not be taken lightly. Tomorrow is never promised, yet there is always the possibility of another attempt.

And this isn’t just wishful thinking. A study published in Nature found that after a first failure, people diverge almost immediately: some refine their next attempt, and others repeat the same mistakes until they quit. The difference wasn’t talent or luck but whether someone incorporated lessons from previous tries.

Failure only becomes useful when it’s examined; without reflection, it simply repeats itself.

IV. How to think when you miss

When a rocket fails to initiate its launch, it reschedules and tries again. This, too, is our opportunity to hit the mark. And that rests on a mindset.

In his classic essay "As a Man Thinketh," James Allen describes the profound power of the seed of thought.

“A man is literally what he thinks, his character being the complete sum of all his thoughts.”

Comparing thought to a garden, Allen emphasizes the importance of planting wisely and pruning consistently.

Often, when we’re discouraged, it’s because of negligent or lazy thinking—something I’m guilty of often. We let doubts roam freely without any discipline. In other areas of life, this carelessness is more easily recognized. We know not to eat anything in front of us or risk feeling sick. We know speeding carries consequences: the loss of life, or at the very least, a ticket. And most would agree that consuming endless social media or low-value shows leaves us worse off.

However, thought hygiene is often overlooked. Allowing negative thoughts to wander reminds me of the invasive pythons in the Everglades. Many are believed to descend from escaped or released pets. Now they slither wild and uncontrolled, devastating the ecosystem.

Our thoughts can do the same when left unattended. This is why it helps to remember that thoughts are objects—they can be shaped, replaced, redirected. It’s not easy to manage them, especially after years of neglect. Even if you’ve built habits around mindfulness or gratitude, it remains a daily fight. But thoughts are temporary things we can observe, move, and replace. With practice, we can trade them for better ones; thoughts that carry opportunity instead of defeat.

Contrast clarifies thought too. I think of my wife, who came to the U.S. as a refugee. One of her first meals here was a tuna sandwich from a cheap fast-food place. Hardly a gourmet experience. But she remembers it as one of the best meals she’s ever had. That gratitude wasn’t manufactured; it came naturally from perspective. She knew what it meant to have nothing, so even a simple sandwich felt like abundance.

When we miss our shot, we face two thoughts. They always arrive together, one loud, one quiet, and our work is to choose the one that keeps us moving:

I missed. This was a waste of time. I don’t want to do this again.

I missed. But I learned something new. I’m grateful I had the chance and that I get to try again.

The second thought, the one rooted in gratitude, is the only one that leaves room for growth. It doesn’t erase the failure, but it transforms it into something usable, something with direction, not despair.

When it’s difficult to frame your mind this way, think again of contrast. There may have been a time, or there may one day be a time, when you cannot take the shot at all. The moment you missed becomes a testament to an unknown future filled with hope and opportunity.

The true failure is inaction. Which is why the greatest danger isn’t missing but refusing to step back up to the line. As solopreneur Justin Welsh says:

“People are so afraid of failure that they never start. Ironically, never starting is the only form of failure there is.”

V. The math of missing

Missing is mathematical. There’s an answer; you just have to learn it to reach your mark. But more than an answer, the math of missing reveals invertibility: every failed attempt narrows the variables. The more you miss, the closer you are to launch.

As Edgar Allan Poe wrote in Mesmeric Revelation, “Never to suffer would have been never to have been blessed.” Each miss, then, is a small form of suffering, a data point that humbles and refines you. You can curse the equation, or you can keep solving it. Because every time you recalculate, you reduce the error.

And one day, after enough misses, the trajectory holds. The rocket lifts.

It will seem sudden to everyone watching, except to you, who spent all that time learning the math of getting it wrong.

On the walk to my car, I glanced back toward the pad. I wondered if that photographer was already checking the forecast, packing his bag, and planning to stand there again for the next day.

Ah, my soul needed this little burst of optimistic orientation to the old adage, “try, try again.”