The gift of ignorance

When we admit we don’t know, life expands in surprising ways

When I finished college, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. I had a graduate degree in business and an undergraduate in English, but my path didn’t seem straightforward. To make some cash on the side, I opened accounts on a few freelance sites.

I started proofreading and revising résumés. Then one day, someone contacted me about a project. She said she was a copywriter. I wasn’t entirely sure what that was, but I listened to her offer. She wanted me to write the first draft of a webpage so she could edit it for client delivery. It sounded like an interesting opportunity, so I accepted it.

I wasn’t sure where to start. The blank page looked more intimidating than jumping out of a moving boat. But I pressed on and delivered a page. The copywriter hired me one more time, but I never heard from her again. My guess is that my work created more problems than solutions. I wasn’t very good at it. Why would I be?

I was entirely ignorant of the craft and the skill. But it launched me on a journey where I would one day write for notable brands all over the world.

Ignorance is one of the most beautiful gifts we have. It means we don’t yet have the knowledge for something. And if we have the self-awareness to acknowledge this ignorance, it opens an entirely new world of opportunities.

II. Why ignorance isn’t the villain

When you visit a news website or scroll through social media, you’ll often see the word ignorance thrown around—especially in the comments or trending tabs. If there’s one word people enjoy using against those with opposing political or worldview stances, it’s “ignorant.” That’s one use for the word, but it does the term an injustice.

There is nothing wrong with ignorance. In fact, it’s a good thing. We are all ignorant in the beginning. Confucius, in The Analects, describes its nature:

“When you understand something, to recognize that you understand it; but when you do not understand something, to recognize that you do not understand it—that is understanding.”

Recognizing our own limits is the first step toward the awareness that everyone’s understanding begins somewhere.

F. Scott Fitzgerald says it best in The Great Gatsby when the narrator observes:

“Whenever you feel like criticizing anyone… just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.”

Fitzgerald hints that personal experience and perspective are what bridge the gap between ignorance and wisdom.

This brings up an important point: where there’s ignorance, there is also a judge—and too often, the judge harms the learner before they ever have the chance to grow.

Steven Foster, writer of Siesta in the Storm, offers a better approach. He says, “I do believe there could be a greater cultivation of what it takes to extend mercy to another on the frontier of one’s own experiences.” Those who spot ignorance should act as helpers and guides, rather than critics.

Ignorance itself is a good thing. The prolonged ignorance of something, however, can be damaging. But isn’t everything that becomes excessive or unchecked harmful in its own way? That shouldn’t take away from the humble beginnings of ignorance.

Arrogance, on the other hand, is the true antithesis of ignorance. It says, “I know I’m right. I will not accept new information.” Where ignorance and humility create opportunity, arrogance stems from pride and the rejection of growth. As Shakespeare writes in As You Like It:

“The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.”

When we can recognize moments of ignorance in our lives, we can ask the right questions—questions that lead to new understanding and opportunity.

III. The joys of not knowing

When you search or chat with AI, it’s easy to forget what it feels like to not understand something, because you get instant knowledge. But as the saying goes, the more you learn, the more you realize how much you don’t know. I’ve felt this many times across a wide range of subjects.

Years ago, I had questions about the quality of olive oil. That curiosity led to one book, then many others. Now I know a fair amount about the topic—not as an expert, but as someone one step closer to understanding. The same has happened with Basque history, the history of cod, quantum computing, and the building of Brunelleschi’s dome in Florence. At first glance, these topics seem unrelated, but over time, they start to connect in unexpected ways, creating new perspectives and creative solutions.

A few years after its 2009 release, I came across a TED Talk on biomimicry that deepened this idea. It fascinated me that nature could inspire answers to some of our most complex problems. A leaf, for example, can teach engineers how to design roofs that direct rainwater efficiently. One lesson from the talk was how innovation grows when people invite experts from unrelated fields to share insights. Even modern philosophers, for instance, can help shape today’s discussions around AI ethics, policies, and design.

This cross-pollination reveals the true beauty of ignorance. Each expert brings deep knowledge in one field, yet remains ignorant of the one they’ve been invited to explore. Their unfamiliarity allows for fresh insight. Likewise, those already in the room may be experts in their own domains but unaware of something vital that could illuminate their toughest problems.

IV. How to stay humble when you think you know

At the risk of becoming arrogant, it’s always better to assume yourself ignorant—even as an expert. There is always a new angle or development to learn from.

Recently, I was reminded by a good friend of mine, Jeremy Ginn, who’s gifted at making new friendships and building people up throughout life. He compares learning to the relationships he makes by saying:

“I approach learning the same way I approach connection. Always do it.”

Living by this outlook ensures we’ll always turn our existing ignorance into growth.

While this posture helps us benefit from most forms of ignorance in life, there will come a time when something catches us off guard—and it may be too late.

Arrogance creeps in, like when Blockbuster didn’t see the sense in Netflix and suffered bankruptcy for it; when BlackBerry balked at the iPhone; or when Spotify defied all odds by democratizing access to music. Ignorance isn’t the failure. The refusal to see it is.

The most effective way to recognize these moments of ignorance is to first spot the challenge. When a person or circumstance challenges what you’re certain of, don’t dismiss it. Ask why. Hear them out. If it’s a circumstance that challenges your thinking, experiment and test the idea.

In a financial sense, it’s like zero-based budgeting. Instead of reusing last year’s budget and editing as you go, you start at zero and add back the essentials. With this approach, you’re more likely to uncover new savings. Similarly, starting with a clear mental slate can reveal the ignorances and opportunities we’ve overlooked.

Early in life, for example, Mark Twain had some success with business ventures and side hustles. His older brother, however, failed repeatedly at business. However, Twain eventually went bankrupt due to a series of poor financial decisions. Much of Twain’s adult life was overshadowed by anxiety from those failures. It wasn’t until he focused on what he was truly good at—writing and humor, and his reading tours—that he regained his financial success, confidence, and self-worth.

But to turn that awareness into growth, we must step outside the safe borders of what we already know.

V. Learning from the unknown

We often strive for comfort, but we miss out on growth by avoiding the unknown. Placing ourselves in unfamiliar circumstances adds new opportunities for learning.

I’m reminded of a moment when I met a home water filtration saleswoman during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. In a clever way, she crafted her pitch to make it sound as though the city had sent her. I caught the trick but overlooked it because she seemed kind, and it was a difficult time to sell anything. While my wife nervously watched, unsure how the new virus spread, I listened to the entire pitch. I didn’t have the money to buy a water system, but I didn’t cut her off. Instead, I treated it as a free class in direct sales—one I still remember today.

Interruptions are the best time to invite learning opportunities. The people you might normally pass on your walk, or the person sitting alone at a coffee shop, have a lesson, story, or perspective that could transform your life.

This realization connects you to sonder—the idea that each person has an inner life just as complex and rich as your own, filled with unique perspectives, emotions, and thoughts. We are all ignorant of the lives of those around us, even the people we know best. That ignorance is an incredible opportunity—an open gate to a vast wealth of knowledge that can both deepen your relationships and expand your own life.

There are many ways to invite moments of learning into your life. Try some of these out:

Join community clubs with random interests, so you’re brand new to the topic

Choose the first book you see in the nonfiction aisle

Read a novel in a genre you rarely touch

Budget your time to stop and have deeper conversations with strangers

Take an online course on something new

Experiment and tinker with ideas, hobbies, and business ventures

Ask “why” about everything you do out of instinct

Travel to a nearby place you’ve never explored, even if it’s just a different neighborhood

Observe someone’s work or craft in silence before asking questions

Each of these small acts of curiosity expands your understanding of the world and softens the arrogance that often grows from routine.

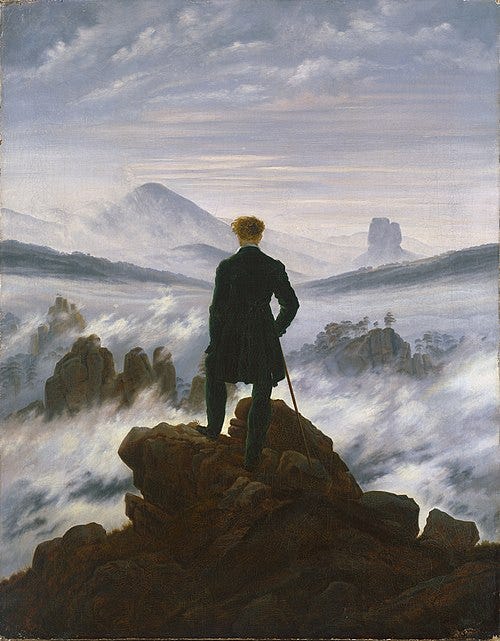

In embracing ignorance, you open yourself to endless ways of learning—about others, the world, and yourself. David Whyte once said in a talk:

“How do you know that you’re on the right path? Because it disappears—that’s how you know. How do you know that you’re really doing something radical? Because you can’t see where you’re going—that’s how you know. Everything you’ve lent on for your identity has gone. And so you are going to enter the black, completive splendors of self-doubt—at the same time as you’re setting out on this radical new path.”

This—unknowing, but with purpose—gives meaning to ignorance. Ignorance is the gap that leads to achievement. It is the promise that something worth pursuing still exists. It is a kind of wondering, a reaching toward the unknown with hope. As Tolkien writes in The Lord of the Rings, “All that is gold does not glitter, not all those who wander are lost.”

The second half of that quote—“not all those who wander are lost”—has taken over memes on Pinterest, decorated bookmarks, and been scribbled across old pianos and bookstore windows. But the first half, “all that is gold does not glitter,” carries an overlooked truth.

Gold is something we recognize, something we know. Yet it may not live up to expectations. It may not glitter. In this sense, gold represents knowledge and expertise—but that doesn’t mean it’s complete.

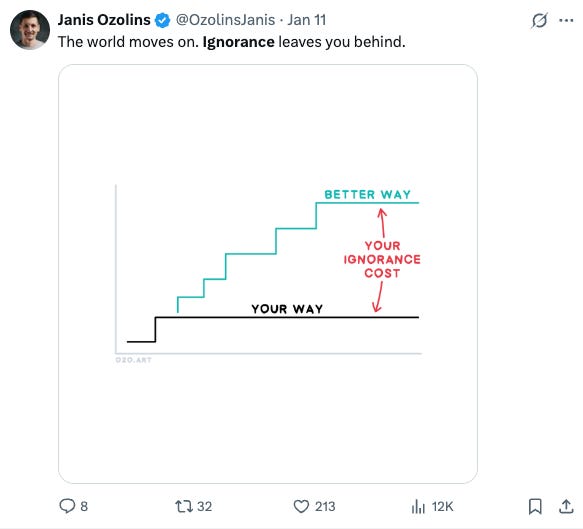

The illustrator Janis Ozolins, a friend of mine, expresses this difference beautifully by contrasting our current way of doing things with the “better way”. Ignorance stands in between. And by closing that gap, we can reach higher achievements.

When we assume our gold is the pinnacle of understanding, arrogance sets in. True brilliance, the “glitter,” comes only from the awareness of our own ignorance and the humble pursuit of what is still new and different.

Thanks for featuring my work. Appreciated.