Why great ideas often come from the wrong people

How amateurs, outsiders, and the simply curious expand what experts miss

Recently, I noticed an article arguing that soybean oil might be a major contributor to the Western obesity crisis. In an X post about it, several replies said something like, “Finally. This concern is being taken seriously.”

It reminded me of early COVID-19 debates, when certain ideas were brushed aside or minimized, only to later be proven partially or entirely true.

Moments like these reveal something fragile about public discourse today.

We hesitate to engage ideas we can’t yet prove. We fear the wildfire of conspiracy theories, and rightly so. But we forget that every true thing begins as something unproven: a theory, a “what if,” or a quiet suspicion that deserves examination.

When we shut down the “what ifs,” we stunt public intelligence and shrink our collective room to explore new truths.

II. Ignorance as a doorway, not a defect

In The Gift of Ignorance, I argued that ignorance isn’t inherently bad. It is a starting point, a doorway. The danger comes when ignorance hardens into arrogance and when the amateur becomes so certain that curiosity dies. But humility in the amateur is powerful:

New eyes bring new perspectives.

Naive curiosity can notice patterns the expert overlooks.

Coincidences sometimes deserve a closer look simply because someone was willing to ask the question others ignore.

When established schools of thought reject novelty, it often comes from fear: fear of disruption, fear of loss, or fear of rewriting what they have already built. Innovation threatens comfort. But fear also exists on the other side. Misinformation can harm institutions, reputations, and entire fields of study.

Both fears are real. Both must be acknowledged.

This tension becomes clearer when we look at how theories form—and how they fracture.

III. Where theories go wrong and where they begin

Some theories, like flat earth claims or moon landing denial, cause cultural and educational decline. They spread quickly because they are dramatic, offer a simplified escape from reality, or feed existing distrust of institutions. The theories function as interesting thought exercises but rarely evolve. They begin and end in the same place: unfalsifiable, self-referential loops.

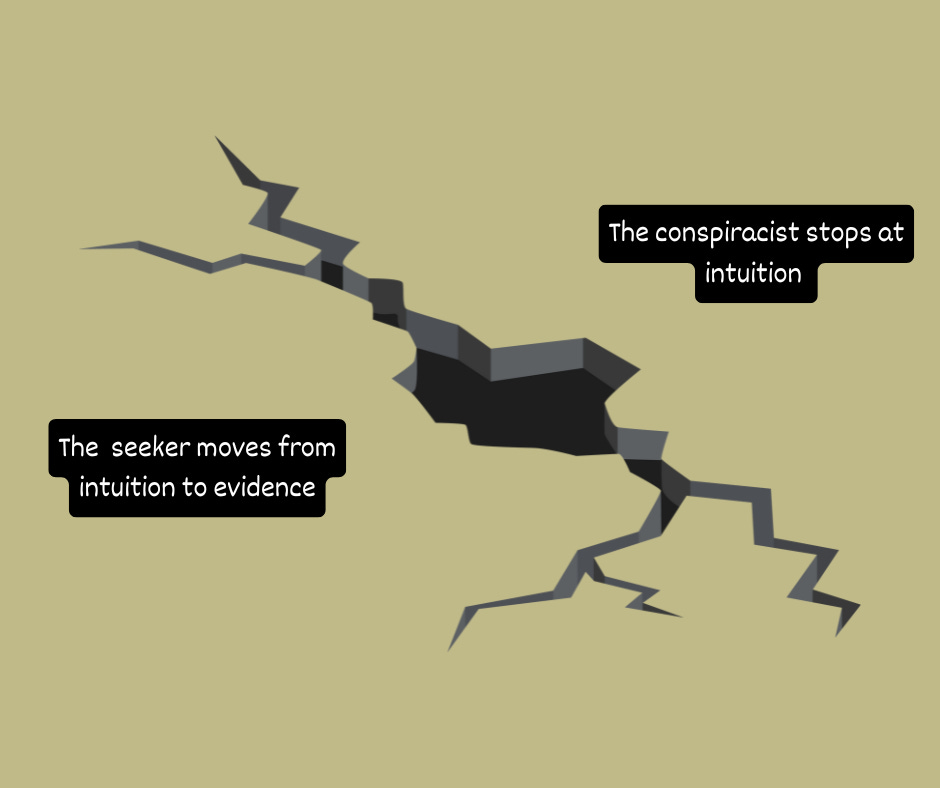

Beneath the cultural baggage, though, a conspiracy theory is still a hypothesis—a claim without evidence, pointing toward an alternative explanation of events. The “conspiracy” label simply adds context: it is a theory that contradicts what most people believe to be true. All unknown truths start here, with a hypothesis, with gut and observation, and with someone willing to test the idea. That is the dividing line:

The true seeker moves from intuition to evidence.

The conspiracist stops at intuition alone.

But bad theories are not the only threat to truth; rigidity within expertise can be just as limiting.

IV. When expertise becomes a barrier to truth

Experts give us the best version of truth we have at the moment. As new evidence arrives, they should update their conclusions. Nutrition science is a good example; its guidance evolves because the evidence evolves. But expertise also carries incentives: status, security, and financial interest. These forces can tempt experts to defend the status quo instead of the truth.

So when an amateur proposes an idea, it is often dismissed before the scientific method can even begin. No testing, no inquiry, no honest evaluation. Only rejection. This disdain extends to self-education. Someone who teaches themselves—reads voraciously, studies independently, and experiments consistently—can still be labeled “undereducated.”

Bruce Weber’s New York Times obituary of Tom Stoppard (the award-winning playwright) illustrates this tension. He writes:

“A voracious reader but otherwise remarkably undereducated for a writer of such voluminous knowledge and understanding…”

The line drew criticism for elitism. Weber contradicts the entire statement with “such voluminous knowledge and understanding.” Even if he didn’t intend the assumption, the remark exposes an underlying belief: education only counts when it comes from an institution.

But Stoppard—self-taught, relentless, and curious—was far more educated than the average graduate. I would argue he was not undereducated but overeducated, in the truest sense.

I once posted on Threads that a self-motivated learner can surpass a college graduate through reading, networking, and a passion for knowledge. The post went mildly viral, and some academics attacked the idea as if I had dismissed formal education entirely.

I hadn’t. I value institutional education. I’m grateful for my degrees. But curiosity does not need permission to search for truth, and it can lead to outcomes as rigorous—and sometimes more rigorous—than formal learning.

We also have countless examples of outsiders improving fields, not out of ignorance but through cross-disciplinary brilliance. Biomimicry borrows engineering solutions from nature. Philosophers advise AI companies on ethics. One neonatal team even invited Ferrari’s Formula 1 pit crew to study their chaotic handover process. Watching how pit crews transfer responsibility in seconds with flawless coordination, the doctors adopted similar role assignments and communication habits. The redesigned protocols helped save newborn lives around the world. The insight wasn’t technical; it was perceptual. The outsiders simply saw what insiders had stopped seeing.

Inviting the “non-expert” does not mean inviting someone who knows nothing. It means inviting someone who knows something different, something the field lacks.

V. Rediscovering curiosity in an expert-obsessed world

When we allow honest dialogue with unfamiliar people and unfamiliar ideas, no matter how odd, naive, or unpolished, we expand our capacity to see what we have been missing.

Everyone is an expert in something: a profession, a hobby, a life experience, a hardship, a culture, or a way of observing the world.

If we honor these forms of expertise, both formal and informal, we give institutions room to grow, ideas room to breathe, and truths room to emerge. The pursuit of truth has never belonged exclusively to the credentialed. It belongs to anyone willing to investigate with humility, curiosity, and integrity.

That is how knowledge moves forward—not by silencing the amateur, but by listening for the insight tucked inside their quiet, “I’m not an expert, but…”