Ugly pumpkins

And the cost of perfection

A couple of years ago, I remember driving on a warm Saturday morning, the car smelling faintly of coffee and musty car seats, on a mission to find a pumpkin patch in Miami Lakes.

My wife and I wanted to take pictures with our two toddlers and take home a pumpkin or two so we could display them on the front porch for Thanksgiving. After some searching, we found a Methodist church with pumpkins displayed on pallets throughout its green front yard.

There were many types of pumpkins, from tiny to giant ones. Most of them, though, were what you would expect: big, plump, orange pumpkins, perfectly rounded, surrounding the yard. With the exception of some white pumpkins, this was almost all there was.

But in the dark corners of the patch, if you looked carefully, you would find the ugly pumpkins—full of warts, a mix of colors like green, yellow, and brown; crooked and viney, leaning toward the direction of the sun.

While initial reactions might balk at these ugly pumpkins, they reveal something about modern culture.

We chase perfection, but what we get in return isn’t beauty—it’s uniformity. And if everything is the same, then is it actually beautiful?

I didn’t realize it then, but those misshapen pumpkins were more memorable than any perfect one I could photograph. Maybe meaning hides not in what’s flawless, but in what we overlook; the hidden beauty. Those pumpkins stayed in my mind long after that morning and made me wonder why we expect them all to look the same.

II. Why we expect sameness

It’s human nature to want to fit in.

We can see this in group identity by analyzing passionate followers of political parties, community groups, and cultural or religious movements. Some of these identities are healthy, like communities that promote charity and positive customs. But others spark issues like friction and divisiveness.

At the heart of all these identities is the need for belonging.

Everyone deserves to feel like they belong. But when it comes to choosing what the masses think is beautiful or important, it’s a combination of this need for belonging and a sense of FOMO. We fear being different, so we become the same.

Even the elements that make us feel individual and different, a common Western value, are often at odds with the truth. Yes, many people choose to wear a different style, dye their hair, or listen to certain music to differentiate themselves from the majority. But those choices signal a certain group and identity that already exists. It’s not truly different; it’s just niche.

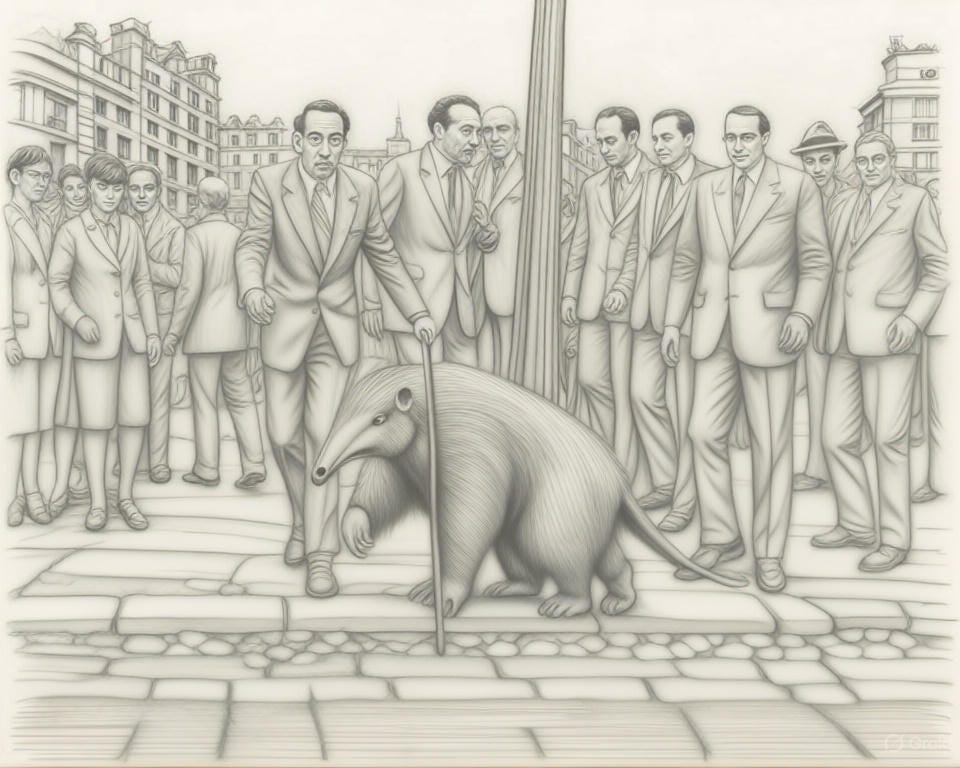

When I think of things that are truly different, I can’t help but think of Salvador Dalí. He was so eccentric that his eccentricity became his identity, and it was so distinct that everything he did made headlines.

As Dalí once said, “I don’t do drugs. I am drugs.” He didn’t need to imitate to stand out. His difference was simply the natural expression of who he was. To be different, we don’t need to be eccentric. But we do need to be authentic to ourselves.

When we visit pumpkin patches to pick the perfect pumpkin, the idea of “perfect” is already in our heads. It’s a round, orange pumpkin. But why do we, at least in North America, imagine one pumpkin out of the estimated 800 varieties? It’s because we have a built-in image of what is accepted, what is beautiful, and what is important.

Among these 800 varieties, each one also varies—it morphs, produces different types of blotches, colors, and warts. And it’s in these differences that these pumpkins are beautiful, despite the lack of celebration for this variety.

However, when you look at other items like sourdough bread, many people rejoice in the diversity of the gas bubbles, the crust, and how these elements develop. Or they admire the diversity of species in a jungle. Why are these celebrated but not others?

Perhaps it’s because of our conception that beauty exists within boundaries or an accepted framework.

Sourdough bread should look airy and bubbly; within that scope, it’s considered beautiful.

A variety of bird species look wonderful in the Amazon jungle because we expect unusual and remarkable species to be there.

On the other hand, if you find an abandoned or dilapidated farmhouse on the outskirts of Italy, with vines wrapping rugged stones, it’s charming; in an impoverished area, it’s seen as off-putting.

Similarly, a pumpkin in the fall should look typical—because that’s tradition. Outside those lines, it goes against tradition.

III. The cost of perfection

When we chase perfection, we trade curiosity for control. A perfect world leaves no room for surprise or discovery. The same happens in our lives: we polish our résumés, filter our photos, and curate our homes until they all start to look the same.

Perfection is deceiving. It promises peace but often delivers the opposite: anxiety.

The fear of being imperfect silences the experiments that make life interesting. Anne Lamott describes this reality in Bird by Bird:

“Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor, the enemy of the people.”

If perfectionism and the pursuit of uniformity are oppressors, then imperfection is the only act of freedom left to us. This craving for control doesn’t just stifle creativity, but blinds us to the quiet beauty already around us. I’ve felt that pull myself; the pressure to present a polished version of life, as if smoothness were proof of worth.

IV. The beauty in imperfection

When we’ve accepted sameness and a limited view of what is beautiful, we lose the opportunity for new experiences—for meaning. Once all our tastes are uniform, we deny the wonders of creation and place it in an unchanging box. But meaning comes from contrast, not control.

Sir Oscar Wilde captured this idea of aiming for ideal perfection in The Picture of Dorian Gray. While the protagonist maintains his youth, he sees his portrait become lifeless as it shows the real truth and perversion of his aim.

Take, for instance, wax seals for envelopes.

There was a time when this was the main way to seal an envelope. If senders only wanted wax seals for practical reasons, they would’ve used blobs. Instead, many used stamps with beautiful designs for their initials or symbols. Today, we may only use sticky residue to close envelopes—a downgrade focused on convenience—but these original wax expressions are still celebrated. The more unique they are, the more meaningful they become.

The Japanese artistic and philosophical movement of wabi-sabi also expresses the beauty of imperfections and uniqueness. The Japanese idea of wabi-sabi celebrates the beauty of imperfection—like a chipped bowl, a faded wall, or a shadowed room. Meaning deepens through wear, not despite it. Wax seals, too, carried that same personal imprint: unique, fleeting, never uniform. Whether in the ornate stamp of a wax seal or the chipped edge of a ceramic bowl, the mark of human touch turns the ordinary into something alive.

To reverse sameness and find meaning in truth, we must first appreciate the unique and rough things and start seeing wonder in their shapes.

V. Ugly just means different

In essence, something that is undesired because of its difference is only ignored because it goes against the grain of expectations. Something that is different, however, opens the doors to new artistic movements, memories, perspectives, and experiences in life.

Literary agents, for example, know what people want. But great agents look for something unique—the “aha” moment that adds to an already existing conversation but isn’t overused or morphed into a well-worn cliché.

When Mary Shelley published Frankenstein, it was so unique that it received passionately mixed reviews. In one review, critic John Wilson Croker said:

“What a tissue of horrible and disgusting absurdity [it] presents.”

Yet it was this work that cemented her legacy and launched the modern horror genre we know today—not because it was similar to the novels of her day, but because it stood in contrast to them.

Once we understand that “ugly” often just means unseen, we can begin to choose differently, on purpose.

VI. Choosing “different” with purpose

The next time you follow a tradition, like choosing a pumpkin or planning an anniversary, think about challenging the status quo. I guarantee people will remember it long after.

Choosing something different is a commitment to a new experience and to finding beauty in the overlooked things in life. It’s often in these moments that you meet a person who changes your life or find a new skill or hobby that alters your trajectory.

These opportunities don’t happen by living the same today as tomorrow or by following what your community says you should do. They start where few people bother to look, among the crooked stems and warty skins I once saw in that Miami patch, where beauty waited quietly, unnoticed, yet entirely alive.