The strange history and quiet wisdom of Spanish moss

How an unruly plant surprisingly thrives

There’s a folktale about Henry Ford touring the South and admiring the strands of Spanish moss hanging from the trees. Struck by its softness and springy texture, he decided to use it as cushioning for his car seats.

But soon after, the moss began to grow from the upholstery, and the mites that had survived within it turned every ride into an itchy, unpleasant experience.

There’s no real evidence this story ever happened, but it’s a captivating myth.

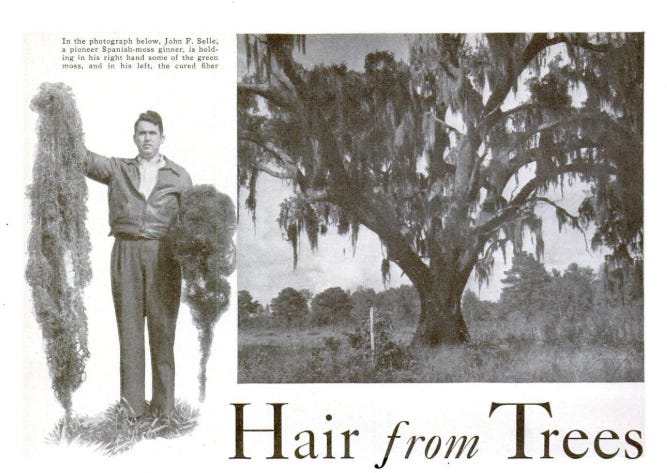

What is true is that companies once harvested the moss for upholstery. A 1937 Popular Science article titled Hair from Trees reported:

“[…] in the last twelve months, more than 20,000,000 pounds of this vegetable hair went into the upholstered seats of streamline trains, transcontinental buses, airplanes, yachts, and deluxe trailers, as well as into mattresses and household furniture.”

A tour guide in the marshes of Vero Beach once told this story to my group, his voice colored with years of retelling. Since then, the image of that wild, living moss bursting from the seams of Ford’s machines has stayed with me.

Spanish moss has no roots. Native to the Americas, it lives suspended on the branches of trees, yet it isn’t a parasite. Its silver strands draw water from the air, thriving on humidity and light.

This moss doesn’t merely survive; it flourishes. It lives without taking, anchored only by the wind, yet still humble. And there’s something in its nature worth learning from.

II. A forest without roots

Spanish moss drifts from branch to branch, carried by wind or birds that weave its threads into their nests. A single strand can become a forest, spreading through fragments that catch and cling wherever the air allows.

The moss prefers to nestle in southern live oaks and bald cypress, trees that leak small treasures of calcium, magnesium, and potassium through their leaves. These quiet exchanges sustain the moss without harm. Only when the strands grow too thick, shading the leaves, does the tree’s growth slow.

Within its tangled layers, there is abundant life. Rat snakes hide among its tendrils, and bats rest in its shadows. A tiny jumping spider, Pelegrina tillandsiae, lives nowhere else on earth. The moss is a small ecosystem.

Today, humans use it in crafts, garden beds, and the crèches of Louisiana nativity scenes. Even the so-called “swamp cooler” of the American desert uses dried Spanish moss to cool homes through evaporation. What I find interesting about these plants is not that they necessarily live rootless, but that they are adaptable and become their best only in the presence of change.

III. How to grow where you land

The nature of Spanish moss is to find its place by way of wind or bird. But once it lands, it grows and spreads. Perhaps we, too, should never cement ourselves in one place, interest, or job, but instead seek the spaces where opportunity and purpose meet. With time, we can grow wide and far, always willing to change.

As we adapt to shifting circumstances and thrive, others, like the spider, may find refuge in our shade. And we will prove useful through the skills and gifts we carry.

Yet while Spanish moss is resilient, it is not immortal. It thrives in humidity, but in the presence of smoke, it withers. Pollution and city air drive it away. In the same way, our own environments, the people we surround ourselves with, and the influences we allow in, will shape our growth and our future.

These principles are noteworthy, especially in a time of uncertainty and turmoil. We truly don’t know what tomorrow will hold. Things surprise us every day, changing society and what we know: pandemics, economic uncertainties, and looming wars. Yet, amid these challenges, Spanish moss is taking over forests.

Susan Orlean, in The Orchid Thief, expresses this idea of nature taking over the present. She describes Florida as the last American frontier. When writing of the Everglades and similar swamps, she says:

“The wild part of Florida is really wild. The tame part is really tame. Both, though, are always in flux: The developed places are just little clearings in the jungle, but since jungle is unstoppably fertile, it tries to reclaim a piece of developed Florida every day. […] Transition and mutation merge into each other, a fusion of wetness and dryness, unruliness and orderliness, nature and artifice. ”

It’s this change, adaptability, and overcoming that make nature and things like moss admirable and worthy of emulation.

Orlean continues her thoughts with a story:

“Once near Miami I saw a man fishing in a pond beside the parking lot of a Burger King right next to the highway. The pond was perfectly round with trim edges, so I knew it had to be phony, not a natural pond at all but just the ‘borrow pit’ that had been left when dirt was ‘borrowed’ to build the roadbed of the highway.”

Similarly, the nature of moss during tumultuous times reminds me that life grows, it tangles, and it evolves through the cracks of uncertainty. The difference in thriving in these times is whether you choose to control the uncontrollable or let go. As the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah writes, “… [my people] have dug their own cisterns, broken cisterns that cannot hold water.”

Perhaps true wisdom is to loosen our grips and learn to understand how we can thrive with what already exists. Moss doesn’t fight the weather but learns its rhythm. It teaches that flourishing isn’t about control but connection, not endurance but belonging.

So it seems the unruliness of Spanish moss isn’t chaos at all. It’s a quiet kind of wisdom: a reminder that growth doesn’t always look straightforward, and it sways with the wind.

Love this!

Thrive right where God has placed you regardless of the circumstances and allow him to fill you into the cracks… What a fantastic article