Jekyll & Hyde was never about a monster. It was about us

How performance, social pressure, and algorithms split us into the selves we show and the selves we hide

There’s a moment (usually a small one, almost throwaway) when I catch myself acting like two different people. Maybe it happens while I’m writing a post, or while I'm hesitating before I speak, or while I'm adjusting some part of myself I didn’t mean to adjust. There’s the version of me who lives, and the version shaped by whoever might be watching.

Robert Louis Stevenson understood that fracture long before we had screens or feeds. In The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, he wrote about what happens when a person is asked to shrink themselves to make another more acceptable.

The story is more than Gothic fiction; it is about a mirror.

The story in three strokes

Dr. Jekyll is a respected Victorian scientist who creates a potion to separate the parts of himself he feels he cannot show the world, and from that experiment emerges Mr. Hyde—violent, unrestrained, and freed from social expectation.

At first, Jekyll believes he can control the division, slipping between identities as if changing coats, letting Hyde carry the weight of desires he refuses to admit.

But the boundary thins, Hyde grows stronger, and Jekyll ultimately discovers that a self, exiled into darkness, does not disappear—it takes over.

Living inside a script

Victorian London taught people to live in straight lines. A life could stretch only as far as its place in the social order allowed, and the boundaries were enforced with quiet, suffocating precision. Certain behaviors weren’t simply discouraged, but they were hidden, pushed under floorboards, buried beneath polite conversation. Stepping outside the approved shape of who you were expected to be meant risking your place in the world.

Today, the pressure looks different but feels familiar. Our “place” is not defined by birth or title but by the soft architecture of digital life: profiles, algorithms, the unspoken rules of visibility. We curate ourselves, trim our edges, and try to become acceptable to both people and machines.

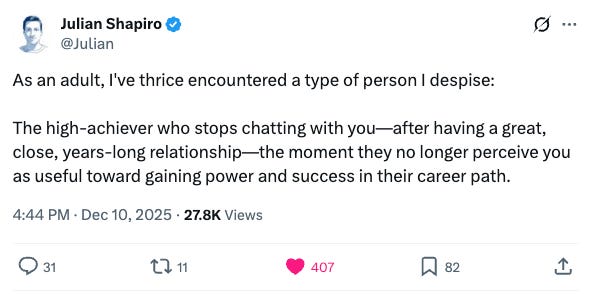

Julian Shapiro recently described how some relationships last only as long as a person remains useful—a subtle, transactional instinct that feels less like a bond and more like an optimization. Even our connections become part of the performance.

Stevenson recognized this machinery long before we had language for it. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is not only a gothic tale; it’s a portrait of any world that prizes appearance over humanity. Through one divided body, he reveals that every person carries two selves: one shaped by expectation, the other by desire.

That tension becomes the story's pulse.

Victorian society carved people into narrow roles: refined, obedient, and controlled. These roles promised stability, but only if the person inside them stayed small. You spoke and behaved a certain way, and even restricted your inner world. Respectability became a costume fastened tightly each morning. Any drift from the script invited judgment or ruin.

A similar pressure hums today. We shape our identities in public spaces where visibility can feel like vulnerability, and self-expression tangles with performance. A “profile” becomes a calling card: a curated version of the self, polished before anyone ever sees it. We learn quickly what is rewarded and what disappears into the feed.

Stevenson collapses these pressures into a single figure. Jekyll isn’t only a doctor with a secret; he represents anyone who has been told, explicitly or silently, to be only one version of themselves. Hyde, the “indecent” self, isn’t an invention but the part of Jekyll that never received permission to live. And the brilliance of the story is not that Jekyll transforms, but that he was already both people.

Small cracks in the social armor

Even characters who never touch the potion reveal the strain of self-containment. Mr. Utterson, steady as stone, carries his hidden warmth like a candle in a locked box. Only in private moments—“when the wine was to his taste”—does “something eminently human beacon” from his eye. A small light leaks through a heavy curtain. We know that feeling today: the relief of speaking freely in a private chat, the ease of being ourselves when no metrics follow us, the softness that returns when we are unobserved.

Poole, the butler, stands at the other end of the spectrum: composed, dutiful, controlled. He looks exactly as society wants him to look, performing his role seamlessly even as the house around him begins to tremble.

Jekyll stands between these figures, pulled by both loyalty and desire. One part of him wants to obey. The other rebels.

Hyde as the door that opens

Hyde isn’t simply rebellion, though; he is release. The exhale after years of holding the breath. A life without the weight of eyes. But in Stevenson’s story, that release quickly mutates. Hyde tramples a child, murders an innocent man, and lashes out with unprovoked violence. He is what happens when a hidden self is not acknowledged and integrated, but forced to grow (and deform) alone in the dark.

Our modern life mirrors this divide. There is the self shaped by algorithms—tidy, consistent, predictable—and the inner self that wants to speak in its own strange cadence, unmeasured and alive. Hyde becomes the shadow-self who slips past the machinery of judgment, tasting oxygen that Jekyll has long denied.

For Jekyll, this feels like salvation. For a moment, he imagines a clean division:

– A public self that can keep its place

– A private self that can slip into the dark unnoticed

“If each… could but be housed in separate identities,” he thinks, “life would be relieved of all that was unbearable.” It is a tempting dream: a life without conflict, a heart without contradiction. But the self is not a building; its walls are thin.

When the hidden self grows teeth

At first, Hyde protects Jekyll. He absorbs the consequences of desire, leaving Jekyll’s outward life untouched. But the moment Hyde steps into daylight, society reacts with force: “the hands of all people” rise against him. The same culture that demanded Jekyll’s silence now threatens his escape. And something irreversible begins.

The part of Jekyll that once asked to breathe now demands space. What he tried to release in small, controlled doses grows stronger each time it returns. The hidden self does not disappear into the shadows but expands to fill them.

This is the danger of exile: what we bury sharpens itself in the dark. Soon, Jekyll can no longer choose his form. Hyde arrives unbidden. The door swings open by itself, and the split he believed he could manage now manages him.

The cost of a single allowed self

Stevenson leaves the reader with a quiet, devastating truth: people cannot survive by amputating the parts of themselves that don’t fit the world’s script. Victorian society demanded singularity, but the human spirit resists such narrow architecture. Our digital age echoes this in softer ways, rewarding polished identities while letting our other rooms go dim.

Jekyll’s tragedy isn’t Hyde, but the belief that Hyde must be erased. A society that fears complexity will always fracture its people. And a person who forces themselves into one agreeable, digestible shape will eventually feel the strain.

Stevenson’s story becomes a lantern placed gently in our hands: a reminder that we are never one thing. The world may reward simplicity, but the self is not simple. It is a home with many rooms—light, shadow, contradiction, and longing. Wholeness comes not from choosing a room but from letting them all breathe.

Removing the filter

For us, the invitation is gentler but not easier: to stop hiding the rooms we’ve learned to keep locked. To let ourselves exist without trimming away the parts that feel inconvenient to the crowd. Living honestly will cost us something—like misunderstanding, indifference, the occasional rejection—but there is a deeper ache in being loved for a version of ourselves we don’t recognize.

And once we stop performing for the invisible gaze, something shifts. The algorithm loses its authority. Growth (online or otherwise) stops being a negotiation with machinery and becomes a slow accumulation of people who meet us where we actually live. It may be quieter, but it is real. And real things last.

The world will always try to make us smaller, simpler, and easier to categorize. But a life built on performance collapses under its own architecture. A life built on truth—even small, steady truth—gives us room to breathe.

Slow growth, slow companionship, slow influence: these are not losses. They are the long, patient shape of a self allowed to exist without disguise.

And if Jekyll teaches us anything, it’s this: the parts of us we hide don’t disappear—they wait, and often, grow uncontrollably.